The complexity of silicate chemistry is formidable. Silicates surround us. The crust of our planet is largely composed of silicate rock in its many forms. Crystalline glazes are one tiny expression of this rich universe of complexity. At the lower level they are just arrangements of atoms, at a higher level of organisation, inhabited by entities such as us with an evolved aesthetic appreciation, they dazzle and excite. A deeper understanding does not detract in my opinion. Richard Feynman, physicist, and an inspiration during my teenage years, puts it very well:

I have a friend who’s an artist and has sometimes taken a view which I don’t agree with very well. He’ll hold up a flower and say “look how beautiful it is,” and I’ll agree. Then he says “I as an artist can see how beautiful this is but you as a scientist take this all apart and it becomes a dull thing,” and I think that he’s kind of nutty. First of all, the beauty that he sees is available to other people and to me too, I believe, although I might not be quite as refined aesthetically as he is, I can appreciate the beauty of a flower. At the same time, I see much more about the flower than he sees. I could imagine the cells in there, the complicated actions inside, which also have a beauty. I mean it’s not just beauty at this dimension, at one centimetre; there’s also beauty at smaller dimensions, the inner structure, also the processes. The fact that the colours in the flower evolved in order to attract insects to pollinate it is interesting; it means that insects can see the colour. It adds a question: does this aesthetic sense also exist in the lower forms? Why is it aesthetic? All kinds of interesting questions which the science knowledge only adds to the excitement, the mystery and the awe of a flower. It only adds. I don’t understand how it subtracts.

Richard Feynman. BBC television interview 1981.

This is a detail from a glaze in development. It produces golden primary crystals set on a pale green opaque ground featuring a thick dusting of golden brown secondaries. The challenge is getting consistent results with both the primary and secondary. I can alter the composition to favour either but the region I’m interested in where both are developed is extremely small and the glaze is unreliable at the moment.

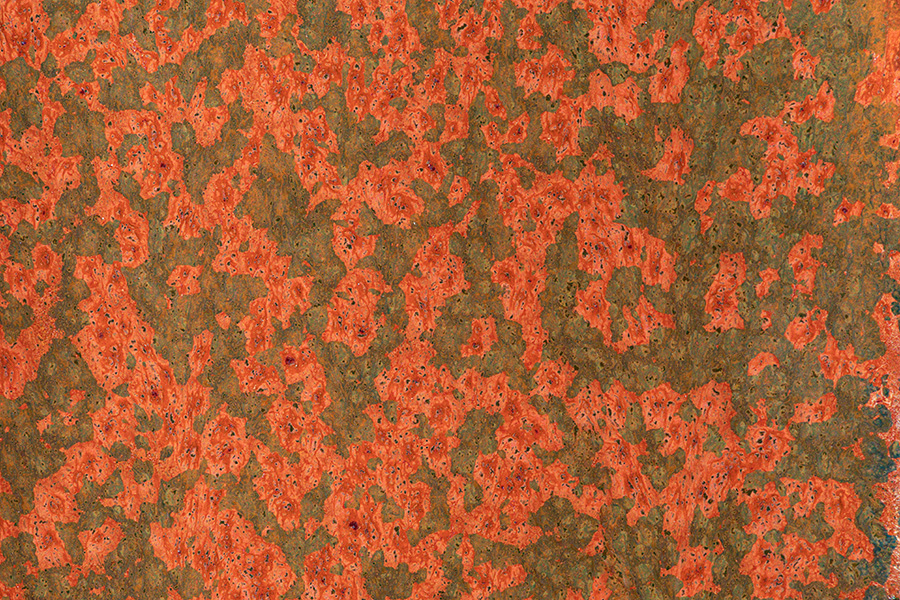

Crystalline glazes based on chemistries other than zinc silicate have been a recent development in my work. The glazes below include examples of my iron red, tea dust and aventurine.

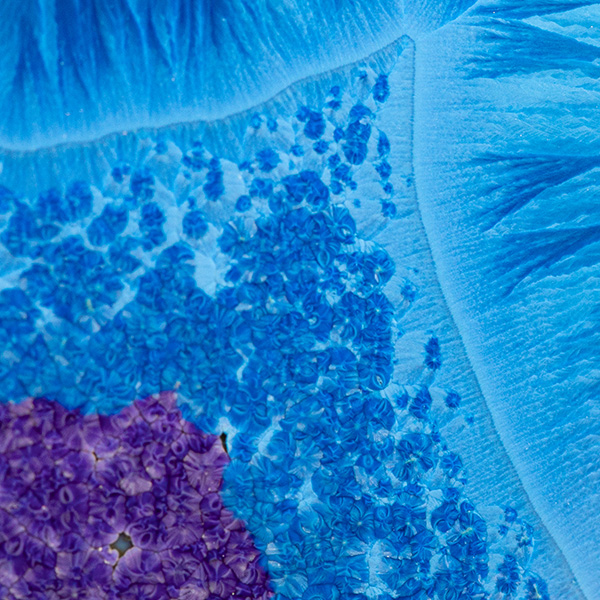

My pale green/blue glaze has many variations – very small adjustments to the balance of fluxing oxides can transform the glaze.

My glazes occupy a niche within a niche: the large primaries are a challenge but getting them together with secondary crystal formation is on a different level of difficulty. Putting a piece through the glaze firing twice often produces additional complexity with the secondaries. I don’t often do this but sometimes a piece comes out not looking as I would like, a second firing is high risk, the failure rate high, but often brings about a spectacular transformation. Many of my favourite pieces are of this type.